The middle muddle

Business Standard, 17 October 2007

In recent months, many claims have been made about exchange rates and macro policy, which are incompatible with the empirical evidence. What appears to be going on is the breakdown of the closed economy worldview. New thinking is required to match the new India.

In recent months, many claims have been made about exchange rates and macro policy, which are incompatible with the empirical evidence. What appears to be going on is the breakdown of the closed economy worldview. New thinking is required to match the new India.

It is claimed that India has suffered a terrible 20% appreciation from Rs.49 a dollar in June 2002 to Rs.39 a dollar today. It seems obvious to most people that such an INR appreciation is completely inappropriate.

However, we need to look deeper at what was going on. Over the same period, the USD has been losing ground, as part of the adjustments required for narrowing the massive US current account deficit. Going by the US Fed's `nominal major currencies index', the USD lost 29.43% over this same period. Going by the `nominal broad dollar index', the USD lost 20.43% over this same period.

We in India are so used to running a pegged exchange rate to the USD, we assume that an INR appreciation against the USD is an appreciation. But our numeraire - our yardstick - is shrinking. If the USD is dropping and we try to hang on to a nominal value of the USD, we are trying to force a depreciation of the INR. This issue is particularly pertinent in recent weeks, when the USD has lost ground rapidly. It may prove to be an important issue in coming months also, where the USD may lose ground rapidly. In the case of the Indian rupee, the appreciation as seen in the REER is much smaller (roughly 10%) when compared with that seen in the INR/USD rate.

It is claimed that INR appreciation would have a terrible impact on exports. However, the empirical evidence does not square up.

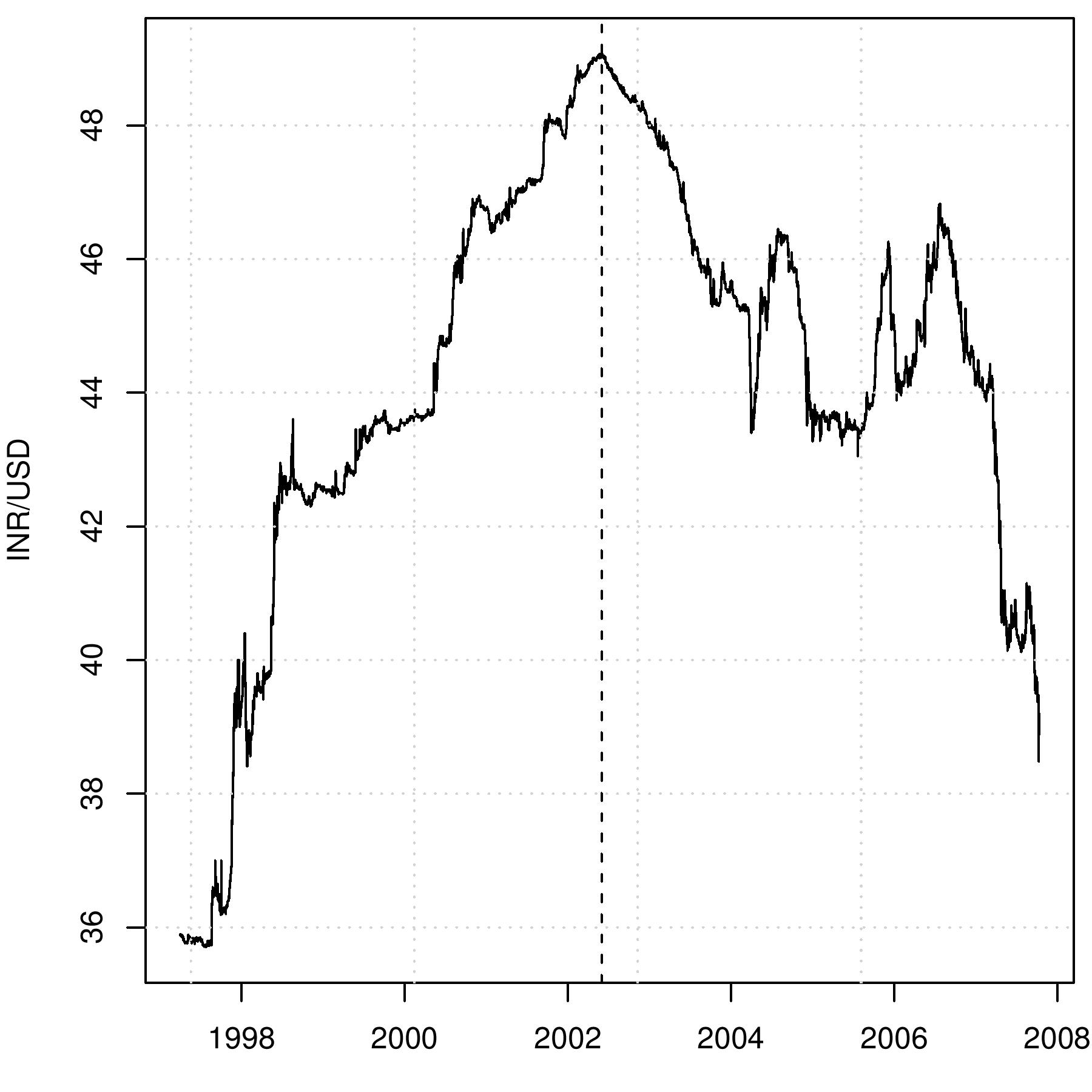

Suppose we focus on June 2002, when the rupee peaked at Rs.49 a dollar. This was 63 months ago. The graph shows the INR/USD series for the 63 months before and after June 2002. In the 63 months that led up to June 2002, exports growth in dollars averaged 6.97% a year. In the 63 months after this date, exports growth averaged 23.88% a year. While the REER appreciated after June 2002, monthly exports of merchandise tripled over these five years. A variety of econometric models show very weak relationships between the REER and exports. Any simple claims about the impact of exchange rate fluctuations on exports are not compatible with the evidence.

Suppose we focus on June 2002, when the rupee peaked at Rs.49 a dollar. This was 63 months ago. The graph shows the INR/USD series for the 63 months before and after June 2002. In the 63 months that led up to June 2002, exports growth in dollars averaged 6.97% a year. In the 63 months after this date, exports growth averaged 23.88% a year. While the REER appreciated after June 2002, monthly exports of merchandise tripled over these five years. A variety of econometric models show very weak relationships between the REER and exports. Any simple claims about the impact of exchange rate fluctuations on exports are not compatible with the evidence.

It is claimed that corporate profitability would be squeezed as firms struggle to maintain export competitiveness. A sharp rupee appreciation took place from 15 March to 6 April. Hence, the April-May-June quarter was the first quarter in which the firms faced a strong rupee. In this quarter, profit after tax of the corporate sector grew by 38.43%. Early indicators for the July-August-September quarter suggest a 30% growth in profit after tax. Bouyant profits are not just about high top line growth: profitability is at unprecedented levels.

It is claimed that a middle path will work, that the old policy framework will get the job done if only government will comply with RBI's policy positions.

A few months ago, a drumbeat was built up about external commercial borrowing (ECB). Every friend of RBI demanded restrictions upon ECB. It was claimed that a middle path is required, with a little unsterilised intervention + a little capital controls on ECB + a little fiscal cost on the market stabilisation scheme (MSS).

This was tried. It did not work.

These mistakes have costs. We suffered the fiscal cost of bigger MSS. We suffered the economic inefficiency of constraining firms on ECB. We suffered the loss of credibility that goes with rolling back reforms on ECB. Most importantly, we are suffering from an inflation process that is increasingly out of control. CPI-IW inflation - the best measure of inflation in India - has accelerated from 6.72% in January to 7.26% in August. Getting CPI-IW inflation back to 3% is the most important macroeconomic challenge that India faces today, and the sum total of policy efforts in 2007 has failed to get the job done.

This is not unexpected given the expansionary stance of monetary policy. Interest rates at the short end are roughly 7%, and CPI-IW inflation is at roughly 7%. The stance of monetary policy is: a real rate of zero at the short end of the yield curve. With a real rate of zero, it is not surprising that we have a boom in asset prices and accelerating inflation. Bringing inflation back under check requires the short end of the yield curve should be atleast three percent in real terms.

Now the drumbeat is building up about private equity flows and participatory notes. Before policy makers accede to these requests for capital controls, the track record of RBI on thinking about economic policy needs to be re-evaluated. There appears to be a gap between the closed economy worldview and the new India, an India that is highly globalised and has new behavioural patterns. The policy reflexes which used to work in the mid 1990s do not work today.

It has long been clear that there is an incompatibility between the new globalised India and the present monetary policy framework. The right way to resolve this incompatibility is to reform the monetary policy framework. India's globalisation, which feeds into India's growth, is more important than the protection of RBI in its present form.

So far, there has been little progress on RBI reforms. What we are seeing, instead, is a campaign that, step by step, seeks to put India back into the straitjacket of capital controls. Budget 2007 brought the denial of tax passthrough for private equity funds unless they were investing in a stated list of industries. Then came the barriers against ECB. Now comes the advocacy of restrictions on PNs and private equity flows. It appears that step by step, focused policy lobbying is taking place on one element of capital account reform, to obtain a reversal of reforms on one element at a time.

I believe this strategy will not succeed. India has come too far along in terms of globalisation. The political economy of capital account decontrol has slipped out of RBI's hands. With foreign investors supplying $200 billion of capital to Indian firms, there is no possibility of a large turnabout on the capital account opening that made this funding possible. The reversal of reforms on the capital account is as infeasible as a project as bringing back high customs duties.

There is no escape for macro policy other than to confront the realities of a large capital account with increasing de facto convertibility. In most countries, central banks have played a leadership role in putting monetary policy on a sound foundation. In India, unfortunately, RBI has failed to display intellectual leadership in correctly understanding India as an open economy, and supporting the transformation of RBI that is required to achieve sound monetary policy.

Back up to Ajay Shah's 2007 media page

Back up to Ajay Shah's home page