Wrong call by RBI

Business Standard, 6 February 2008

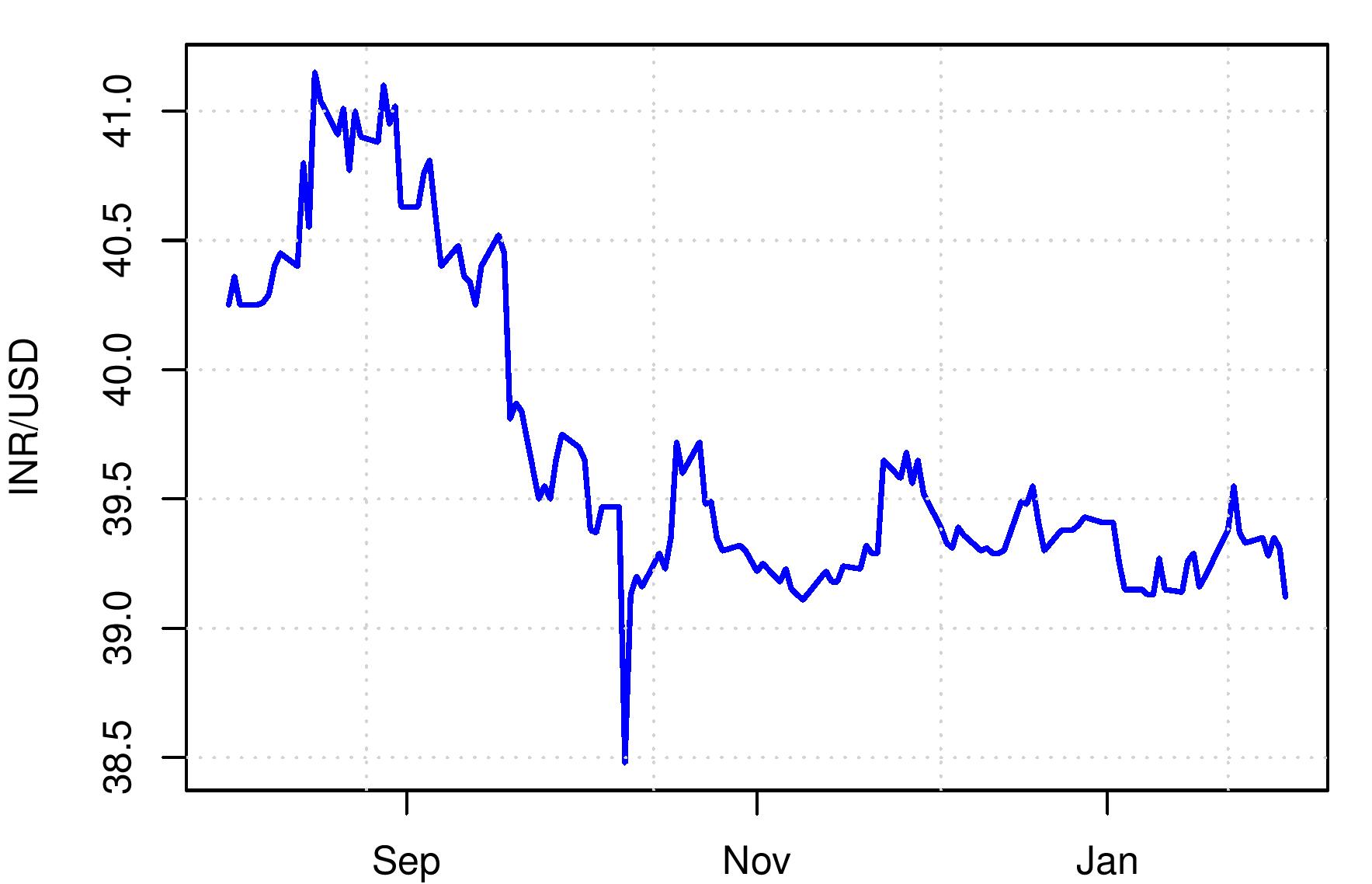

The rupee is tightly pegged to the dollar, with movements between Rs.39 and Rs.40 per dollar. A very attractive `dollar carry trade' has sprung up. The private sector can earn 5 percentage points - without bearing any risk - by borrowing in dollars and lending in India. Fundamental principles of open economy macroeconomics suggest that it is not possible to have a pegged exchange rate, coupled with substantial openness on the capital account, and then sustain a large interest rate differential. The immediate opportunity for every CEO is to feast on the free lunch that has been gifted by RBI. Looking beyond, either the rupee-dollar peg will have to yield, or RBI will cut the short-term rate by 2 to 3 percentage points.

The rupee is tightly pegged to the dollar, with movements between Rs.39 and Rs.40 per dollar. A very attractive `dollar carry trade' has sprung up. The private sector can earn 5 percentage points - without bearing any risk - by borrowing in dollars and lending in India. Fundamental principles of open economy macroeconomics suggest that it is not possible to have a pegged exchange rate, coupled with substantial openness on the capital account, and then sustain a large interest rate differential. The immediate opportunity for every CEO is to feast on the free lunch that has been gifted by RBI. Looking beyond, either the rupee-dollar peg will have to yield, or RBI will cut the short-term rate by 2 to 3 percentage points.

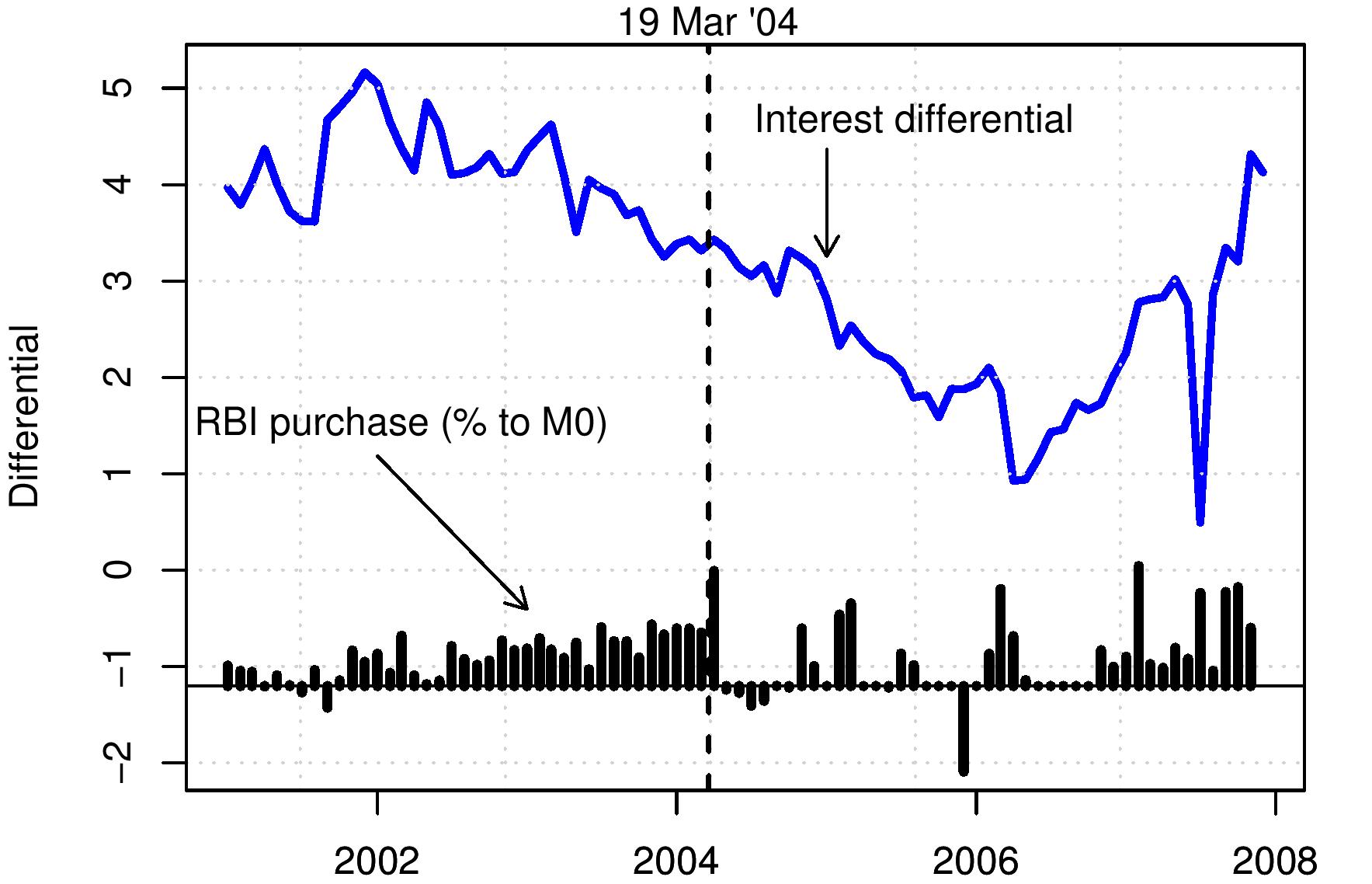

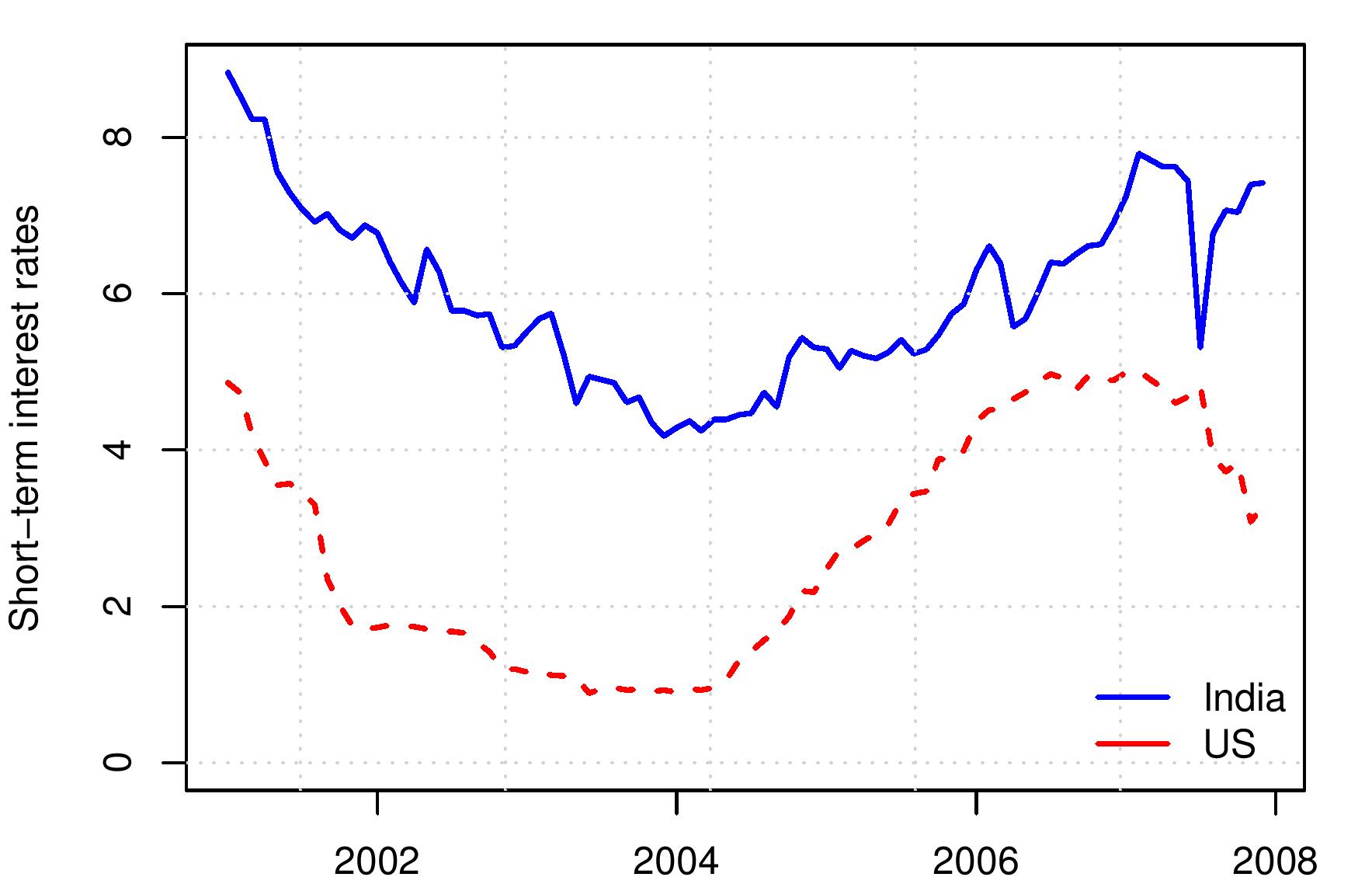

The interest rate differential is best computed between the 90-day secondary market rate on government bonds in the US and in India. It is shown as the blue curve in the graph on the right. Prior to March 2004, very high values - of above 3.5 percentage points - were found. It is not coincidental that at this time, RBI was buying dollars at a massive pace. The barchart superposed inside the same graph shows RBI purchases for each month, expressed as percent of reserve money. This hectic pace of reserves purchase from 2002 to 2004 was unsustainable, and led up to a breakdown of the exchange rate regime on 19 March 2004.

The interest rate differential is best computed between the 90-day secondary market rate on government bonds in the US and in India. It is shown as the blue curve in the graph on the right. Prior to March 2004, very high values - of above 3.5 percentage points - were found. It is not coincidental that at this time, RBI was buying dollars at a massive pace. The barchart superposed inside the same graph shows RBI purchases for each month, expressed as percent of reserve money. This hectic pace of reserves purchase from 2002 to 2004 was unsustainable, and led up to a breakdown of the exchange rate regime on 19 March 2004.

In the period after that, for a while, the stance of monetary policy was more sensible. The interest rate differential was smaller, and exchange rate flexibility was higher. There was less of a one-way bet, and for some time, no pattern of sustained and massive market manipulation of the currency market emerged.

From mid 2007 onwards, we are getting back into danger zone with a large interest rate differential once again building up, coupled with a tightly pegged exchange rate. On 31 January, the 90-day rate in the US was 1.9%. The Indian 90-day rate is roughly 7.2%, yielding a massive differential of 5.3 percentage points. From late-2007 onwards, the rupee has been tightly pegged to the dollar, with tiny exchange rate fluctuations between Rs.39 and Rs.40 per dollar.

Put together, this is a one-way bet. The private sector is being told:

"Borrow at near 1.9% in the US, somehow get the capital into India and get paid near 7.2% in return for bearing no risk at all. There is no risk of currency fluctuations because the rupee is tightly managed. At worst, you'll only benefit because of a rupee appreciation."

Suppose a person finds a way to borrow $1 billion in the US, bring it into India, and earn the interest rate differential of 5 percentage points, over a period of one year. He earns a profit of $50 million or Rs.200 crore for bearing no risk and doing no work (other than jumping past the capital controls). This is an attractive free lunch. If $100 billion now come into the country, it is a gift of Rs.20,000 crore to the private sector assuming a one-year holding period.

Every rational CEO in India is getting his financial advisors to find ways to exploit this arbitrage opportunity. It is not an accident that in the graph, we see RBI currency purchases (expressed as percent of reserve money) once again showing large values month after month. One key factor driving this is the enlarged interest rate differential.

The last time an interest rate differential of five percentage points was found was in 2002. The 2002-2003 period was an unhappy one for RBI where a `reverse speculative attack' led to a breakdown of the erstwhile exchange rate regime. Now, conditions are even more hostile for RBI. India's openness has increased greatly in the last five years. Flows on the current and capital accounts have roughly doubled, as percent of GDP, over these five years. If the policy framework of pegged exchange rate coupled with a large interest rate differential was infeasible in 2002-03, it is even more infeasible today.

The last time an interest rate differential of five percentage points was found was in 2002. The 2002-2003 period was an unhappy one for RBI where a `reverse speculative attack' led to a breakdown of the erstwhile exchange rate regime. Now, conditions are even more hostile for RBI. India's openness has increased greatly in the last five years. Flows on the current and capital accounts have roughly doubled, as percent of GDP, over these five years. If the policy framework of pegged exchange rate coupled with a large interest rate differential was infeasible in 2002-03, it is even more infeasible today.

What is being played out here is a nice textbook lesson in open economy macroeconomics. RBI has not woken up to the fact that India has changed, that India is now a de facto open economy. The maze of capital controls might earn a lot of diwali gifts, but over a trillion dollars still move in and out of the country every year. More than a thousand Indian companies have embarked on turning themselves into multinationals. An offshore subsidary can borrow, thus bypassing capital controls against ECB. Transfer pricing can be used to move capital across the boundary. Trade credit is being utilised for capital flows by all importers and exporters. NRIs send money to family in India, who then buy government bonds.

If capital controls were effective, RBI would not be facing an unprecedented struggle in pegging the exchange rate after having tried to close down ECB and PNs. India has embarked on de facto convertibility on the ground, even if not in the world view of policy makers.

The textbooks teach us that when the capital account is open, pegging the exchange rate gives a loss of monetary policy autonomy. Regardless of what RBI might believe is the appropriate policy rate in India, it has no choice but to keep a differential of no worse than 2 percentage points compared with the US Federal Reserve. By pegging the exchange rate, RBI has bowed out of the game of setting Indian monetary policy. The US 90-day rate is at 1.9%, therefore the Indian short-term rate cannot exceed 3.9% - or else the exchange rate peg has to break.

A separate discussion needs to take place about whether or not pegging the rupee to the dollar is optimal for India. But once the rupee has been pegged to the dollar, there should be no illusions about RBI having autonomy on setting the policy rate.

Mistakes like this are not an accident. The monetary policy framework that worked when India was a closed economy is being unthinkingly applied in a new India. But India has changed. It is wrong for RBI to bemoan this change, and demand that India be forced back into the straitjacket of `holistic' capital controls. On the contrary, it is the monetary policy framework that must change. A new monetary policy framework needs to be constructed, that is designed for a new India that is an open economy.

Back up to Ajay Shah's 2008 media page

Back up to Ajay Shah's home page