Having only a 10-year bond futures is more useful than meets the eye

Financial Express, 7 September 2009

On the equity market, one well known feature of a malfunctioning emerging market is the domination of the market index. When the equity market works badly, there is poor disclosure about companies, so day to day changes in stock prices based on information revelation by companies take place to a limited extent. In badly structured countries, the dominant risk that a company faces is caused by macroeconomics and politics. As an extreme example, the dominant question in Sri Lanka has been about the war. The day to day fluctuations of stock prices were primarily about the outlook on Prabhakaran. They had relatively little to do with information about one company at a time.

In such a malfunctioning emerging equity market, the fluctuations of individual stocks are relatively unimportant, and all that matters is the fluctuations of the stock market index. In international comparisons of this issue, India fares well. In India, Nifty accounts for a proportion of the fluctuations of (say) Jet Airways or (say) Sundaram Fasteners which is relatively small. India looks more like an OECD country in this respect. This reflects the sophistication of the Indian equity market, which (in turn) reflects the correct decisions made in economic policy by MOF and SEBI from 1992 onwards.

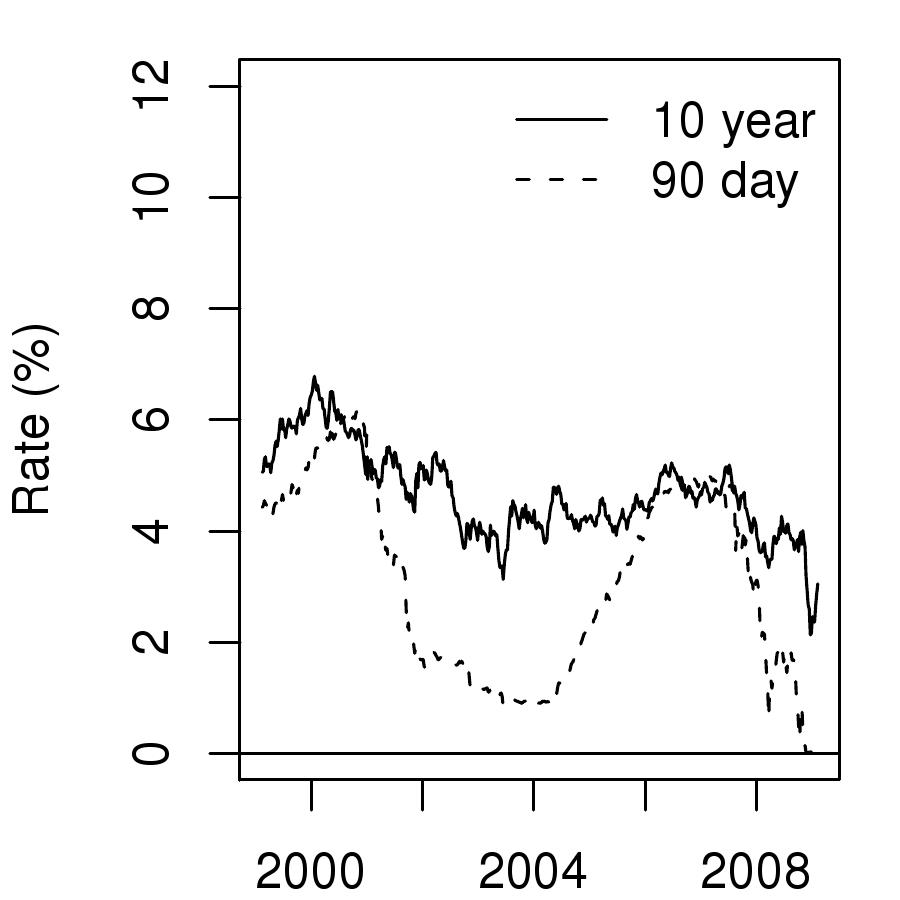

Similar logic applies to the bond market. In a sophisticated bond market, the short-term interest rate and the long-term interest rate have complex reasoning of their own. They do not necessarily move in tandem. There is a liquid market for each of them, complete with analytical ideas, speculators and arbitrageurs. As an example, Figure 1 superposes the 90-day and the 10-year interest rate in the US. It shows substantial movements of the 90-day rate which differs from the movement of the 10-year rate.

Similar logic applies to the bond market. In a sophisticated bond market, the short-term interest rate and the long-term interest rate have complex reasoning of their own. They do not necessarily move in tandem. There is a liquid market for each of them, complete with analytical ideas, speculators and arbitrageurs. As an example, Figure 1 superposes the 90-day and the 10-year interest rate in the US. It shows substantial movements of the 90-day rate which differs from the movement of the 10-year rate.

Both interest rates in the US have had low values, from a minimum of 0% to a maximum of 6%. This reflects the success of the US in putting monetary policy on a sound footing. The US Fed does de facto inflation targeting; long term inflation in the US is pretty likely to be 2%. Hence, the bond market is comfortable giving low interest rates to the economy.

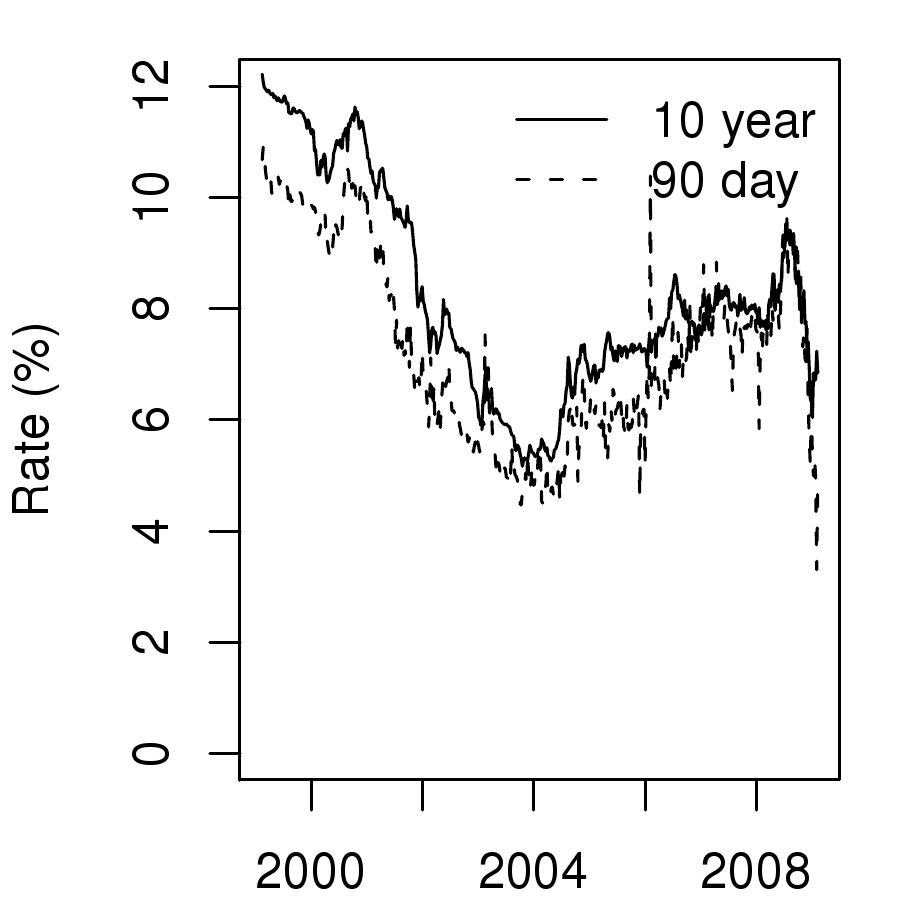

We turn to India in Figure 2. This graph also superposes the 90-day rate with the 10-year rate. The scale of the x and y axes of both graphs are identical, to facilitate comparison. The first point we see is that there is a secular gap in interest rates. India has high interest rates, ranging from 3% to 12%. This reflects the lack of a proper institutional foundation of a central bank. As an example, RBI continues to argue that the accountability mechanism of inflation targeting should not come about in India. There is a simmering conflict in India between politicians (who desire low inflation) versus RBI (which enjoys avoiding accountability). Most modern economists would side with the politicians on this one.

We turn to India in Figure 2. This graph also superposes the 90-day rate with the 10-year rate. The scale of the x and y axes of both graphs are identical, to facilitate comparison. The first point we see is that there is a secular gap in interest rates. India has high interest rates, ranging from 3% to 12%. This reflects the lack of a proper institutional foundation of a central bank. As an example, RBI continues to argue that the accountability mechanism of inflation targeting should not come about in India. There is a simmering conflict in India between politicians (who desire low inflation) versus RBI (which enjoys avoiding accountability). Most modern economists would side with the politicians on this one.

The second interesting feature is the extent to which the two rates move together. There are sharp fluctuations in interest rates. Interest rate risk is a real problem in India. Every borrower or lender faces substantial risk because these rates can change quite sharply in a short time. At the same time, both rates tend to move together strongly. Most of what happens in India by way of interest rate risk is parallel shifts of the curve.

This reflects the pathology of a malfunctioning emerging market. There is not much in India by way of analytical work, speculation and arbitrage on the bond market. The short rate and the long rate do not have much of a life of their own. There is really only one macro shock which takes place each day, which moves both rates. This is akin to being in Sri Lanka in the stock market, where there isn't much price discovery about individual stocks every day; instead there is just overall politics/macroeconomics hitting the market index.

RBI has made important mistakes in a pair of committee reports. The first committee report forced the use of physical settlement, claiming that cash settled interest rate futures are infeasible. This reflected a lack of knowledge of standard textbooks of finance, which teach how to deal with cash settled interest rate derivatives. RBI went on to then block futures on short-term interest rates (despite their having been recommended by the first committee).

These are mistakes of policy, which work to impede India's economic growth. In the long run, RBI has to solve the human resource and incentive problems that are persistently leading to such mistakes.

In the short term, the economy has to now make the best of what it has got. Owing to numerous efforts by RBI at preventing a bond market from coming about, there is not much by way of price discovery of a short bond as opposed to the long bond. There is certain irony in observing that as a consequence, the damage that is done by the most recent mistakes is reduced. All that happens on the bond market is one big question every day: "What is the interest rate". In such a world, the 10 year bond futures alone can be rather useful.

Back up to Ajay Shah's 2009 media page

Back up to Ajay Shah's home page