Is China's loss India's gain?

Business Standard, 29 July 2019

D. Trump has taken the US into a trade war with China. The early evidence suggests some gains from this for India. The deeper gains will arise, however, through the FDI decisions of the boards of global companies, which will play out over time. For India to make the best of this situation, we need to become more of a mature market economy, and play fair by the rules of the game of globalisation.

In a China/India comparison, the Chinese economy is bigger and the Chinese policy establishment is more capable. China has graduated to making sophisticated goods, such as computer equipment, which India does not make. India's exports, so far, look more like those of developing country. As a consequence, we may expect that the US-China trade war might not yield significant gains for India.

In order to assess the developments associated with the trade war, the data to focus on is the US import of goods from both countries. India does well on services exports to the US, but we will keep those out of the analysis as the US-China trade war is primarily about goods. The latest data, for the month of May 2019, shows that India's goods exports to the US were $5.6 billion, China's exports to the US were $39.3 billion and the total import of goods into the US was $220.8 billion. India's value is, of course, much smaller than that of China.

How have the exports of the two countries been changing as a consequence of the US-China trade war? The highest ever value of China's share in US imports was in September 2015, at 23.87%. From that high, there has been a decline to 17.78% in the latest data, which is May 2019. Just one year prior to this, in May 2018, China's share was 21.5%.

From the peak of September 2015 till the latest reading of May 2019, China's share in US imports has declined by 6.09 percentage points. This is a big change. Over this period, India's share in US imports went up from 1.92% to 2.54%. This is a gain of 0.62 per cent. We may say that about a tenth of the share ceded by China has accrued to India.

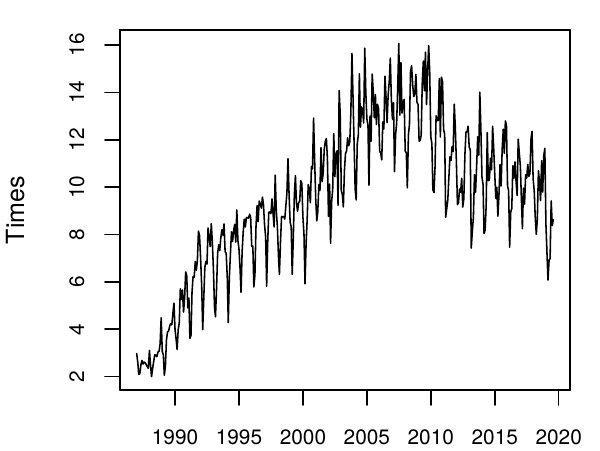

China's exports to the US divided by India's exports the US (times)

To what extent are these changes about the recent trade war, and to what extent is there some deeper long-term phenomenon going on? The graph shows China's exports of goods to the US divided by India's exports of goods to the US. Chinese exports were about 2 to 4 times larger than India in the late 1980s, and this went up to 16 times bigger by 2007.

Over the last decade, the ratio has improved from India's point of view. Over and above this long-term process, it does look like the latest few data points have some greater gains for India. These may reflect a response to the US-China trade war.

How best can India play the emerging US-China trade conflict? The first point to emphasise is that most global trade takes place within multinational firms. When Walmart grows deep roots in India, Walmart will export more from India. For India to do well in exporting, we need global firms to commit to India, on a greater scale, and we need Indian multinationals to flourish. These effects will necessarily play out slowly. When a US-China trade war erupts, in the short run, global firms do not change course by much. But in the medium term, boards of global firms are constantly looking at the countries in which they operate and making changes based on their judgement about the countries that offer a better economic environment.

We have to get into the mind of the boards of global firms, which are grappling with the problem of their over-exposure to China. What can we do to become more attractive to them?

Improving India's attraction as an FDI destination is about the familiar issues of labour law, infrastructure and taxation. Of these, taxation has become a particularly important problem. Tax policy and tax administration is a major concern for global operations. For India to be integrated into global supply chains, goods should seamlessly move into India, and then get re-exported. This requires removing all customs duties, establishing a GST-on-imports and having zero-rating of exports. It also requires well structured operational procedures and a well behaved tax administration. The use of raids and imprisonment deters private persons from operating in India.

India now has the highest income tax rate for corporations in the world, and a source-based taxation system. This needs to shift to a residence-based taxation system, and an income tax rate for corporations (all inclusive) of 20%.

India is seen as a difficult place to operate in, on account of policy risk. There is a danger of sudden change, e.g. in customs duties. This requires deeper reform of the policy process. The process of making laws and regulations requires greater consultation, cost-benefit analysis, and introduction of rule changes from dates well into the future.

We should rein in our sense that China's loss is our gain. India has a lot to lose in the decline of a rules-based world of globalisation. We now earn Rs.4 trillion per quarter from the export of services and Rs.6 trillion per quarter from the export of goods. That is, we earn Rs.0.44 trillion every calendar day through the export of goods and services. We already have a lot at stake in a globalised world. Looking into the future, it is likely that policy reforms in India (on the issues sketched above) will yield considerable growth of exports from India. We will have more at stake in the future.

If Trumpism becomes the new normal, we will be at the receiving end of it at future dates. India's stance in international relations should emphasise the gains from a rules based world of open borders, where there is a low risk of new barriers to globalisation coming up.

Back up to Ajay Shah's 2019 media page

Back up to Ajay Shah's home page